Visit our latest newsletter out today: Spring Tidings from Bridge for Health!

Information on new events, announcements, awards and much more!

Visit our latest newsletter out today: Spring Tidings from Bridge for Health!

Information on new events, announcements, awards and much more!

By Paola Ardiles

Last week I was excited to be invited as a guest speaker at SFU’s Radius social entrepreneurs and innovators fellow program to talk about my experience around building relationships and networks. The 2015 cohort is full of bright, enthusiastic and determined Millennials. I was curious about how my views as a GenX on building relationships would differ from theirs, especially given that they have spent much of their lives somehow connected to technology.

As I started to reflect on how this work comes about in my daily life, I realized that relationships and partnerships are the most critical aspects of my work. In fact, I would argue that relationships are at the core of social innovation.

Have you ever found yourself trying to solve a complex social issue but been stuck on an idea until you actually engage in conversation with a friend or colleague? I often find that just by sharing my place of being stuck, the juices start to flow and by the end of the conversation I have had a breakthrough idea or created an action plan to move forward.

Through relationships you can build solid support for your ideas, no matter how big or small. The fellows asked me specifically about the ‘how’. How can we build relationships in a world where there is so much information out there and so many places to connect not just in person but also online?

(Michael Stone Photograph, with permission)

Relationships are cultivated over time and they definitely do not follow any certain path. My children and the new generation have taught me that building relationships can be very effective through social media and can also be based on reciprocity. I have also come to appreciate that building and sustaining relationships is the most important skill I can bring into my life. It is also like the concept of karma, relationships like opportunities don’t just happen to me, I can create them. I am not just referring to professional relationships. Personal ones can offer you the emotional support and space to be able to create in your work. Interestingly enough, many personal relationships of mine have turned to professional ones and vice versa.

For instance, I have been a close friend of Amy Robinson, Founder and Co-Executive Director of LOCO BC. We both share many common interests and values. Amy and I have cultivated a friendship for the last 5 years, practically since I moved to Vancouver, although it seems like we have been friends for a lifetime. Conversations with her have hugely impacted my thinking.

LOCO BC is a non-profit local business alliance working to strengthen communities, grow the local economy and build strong, sustainable businesses by encouraging a shift in local purchasing by consumers, businesses and institutions/government. Our work is predicated on the belief that economic sustainability, along with social and environmental sustainability forms the bedrock of healthy and resilient communities.

Amy has worked tirelessly over the last decade to create this network and thanks to her commitment and her partnerships, LOCO is thriving. I have been watching her development as a woman and as professional and she is truly an inspiration. So, two years ago when I first started Bridge for Health I decided to join LOCO BC.

The more I was immersed in the world of economics and environmental sustainability, the more I could start to see the opportunities between my work in public health and business. I started to imagine how it could be possible to bring these worlds together as I realized that our visions are very similar.

Today, I am building Bridge for Health as a social enterprise focused on social innovations in health and creating a framework for Healthy Businesses. I am so grateful to have had Amy’s support throughout these years, especially to help through those times of self-doubt and uncertainty.

Of course, I have been influenced my many other friends and colleagues who have exposed me to a wide range of ideas about sustainability, design-thinking, inequities or spirituality. All of those conversations have in fact shaped my views and I am deeply grateful to all who have contributed to my vision, in one way or another.

Relationships can blossom into lifelong friendships or partnerships to help you create the world you want to live into. Never under estimate the power of human connection. It is powerful beyond measure.

And, we must not forget that years of research have confirmed that (healthy) relationships are also very good for our health and wellbeing!

So, next time you are going to tweet, send an email, meet someone for lunch meeting or invite someone for a coffee, remember that relationships don’t just happen to you, they are you. Every word, gesture and smile can have a positive impact to make this a healthier, kinder, safer and more just world.

Paola Ardiles, Founder Bridge for Health

This year Bridge for Health Founder Paola Ardiles has been honored to be a YWCA Metro Vancouver Women of Distinction finalist in the health and wellness category. She was nominated by friends and colleagues from Bridge for Health and Simon Fraser University, as well as the President of the Public Health Association of BC. As a nominee, Paola also has the chance to participate in the Connecting the Community Award to get Scotiabank to donate $10,000 towards preventing violence against women.

This year Bridge for Health Founder Paola Ardiles has been honored to be a YWCA Metro Vancouver Women of Distinction finalist in the health and wellness category. She was nominated by friends and colleagues from Bridge for Health and Simon Fraser University, as well as the President of the Public Health Association of BC. As a nominee, Paola also has the chance to participate in the Connecting the Community Award to get Scotiabank to donate $10,000 towards preventing violence against women.

Paola has chosen to support a YWCA program to prevent violence against women.

“As an immigrant mother, researcher and advocate for women’s health, I have learned that freedom from violence is a critical factor to improve health and mental well-being. Investing in housing is an essential upstream approach to preventing violence against women. I support YWCA’s Munroe House, which offers essential services to create safe environments for women and children escaping violence.” Paola Ardiles

You can vote once per day so you don’t have to choose between any of nominees. All votes go towards a good cause!

Cast your vote today until May 15th, 2015 by clicking HERE and please help spread the word.

Today is not just the first day of spring (or fall in the south), it is also the International Day of Happiness – a day to celebrate the things that contribute to human wellbeing and a flourishing society. Dr. Mark Williamson, Director of Action for Happiness

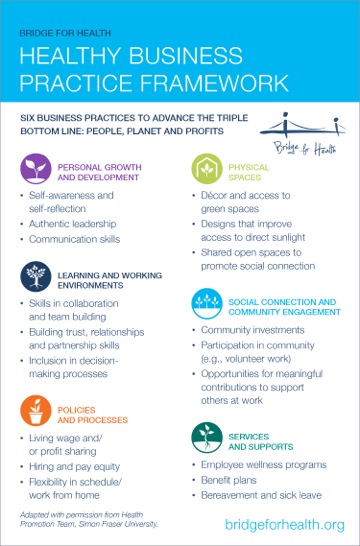

Bridge for Health is celebrating this day by putting forward a Healthy Business Practice Framework to start a conversation on how we can promote happiness and wellbeing in our workplaces.

We spend so much of our adult lives at work, so how can we ensure we are creating happy and healthy environments for individuals, teams, organizations to flourish and reach their full potential? To date there are many interventions around employee health to support individuals to get more active, or choose healthier food choices. Those are all important. However, if we view health as holistic and collective, there are many other areas that are just as important to pay attention to. Especially if we think about the organization or business, and its community as a whole, or as a system.

This model belows highlights six business practice areas and evidence-based examples of practices to promote wellbeing in a business setting, that are aligned with corporate social and environmental responsible practices. It is a starting point and we hope you will join in to provide examples and feedback.

How does your business or organization measure up in these 6 different practice areas?

We are currently collecting stories to post as promising practices and would love to hear from you!

Contact us today at info@bridgeforhealth.org

Reference: Ardiles, p (2015). Healthy Business Practice Framework. Adapted from Healthy Campus Initiative, Health Promotion Team, Simon Fraser University.

Along with over 100 organizations, Bridge for Health is a member of the Better Transit & Transportation Coalition and supports a YES vote in the transit referendum in Metro Vancouver. On March 16th let’s show with our vote that we care about the health, environment, economy and wellbeing of our future generations. Below, Dr. Trevor Hancock shares why investing in public transit is good for public health!

By Dr. Trevor Hancock

Public transit plays a vital role in our highly urbanised societies, one that is particularly important for people who don’t have a car. That includes people with low-paying jobs as well as many children, youth, university and college students and seniors, among others. It helps them get to and from work and to access amenities and services.

Good public transit also reduces congestion, leading to more economically efficient cities, because there is less time and energy wasted in traffic jams; in the USA, traffic delays due to congestion consumed 3.7 billion hours in 2003, and time is money! But beyond these obvious benefits, there are also many public health benefits that result from good public transit. But first we need to understand the health impacts of transportation in general, especially in cities.

Happily, one of the world’s leading experts on this issue is here in Victoria. Todd Litman, Director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, did a review of transportation and health for the prestigious Annual Reviews of Public Health in 2013. He noted that the main health problems associated with transportation include deaths and injuries from traffic crashes, heart and lung diseases due to air pollution, reduced physical activity and increasing obesity, mental health impacts and lack of access to health-related goods and services.

A 2014 World Bank report found that about 1.3 million people die every year as a result of road traffic crashes and a further 78.2 million people suffer non-fatal injuries. Between age 1 and 59, road injuries are among the top ten causes of death. Not surprisingly, as the world urbanises and industrialises, the toll rises; deaths due to motor vehicles have increased almost 50% in the past 20 years.

The World Bank also estimates that 184,000 deaths annually are caused by air pollution due to vehicles; other estimates suggest it is much higher, closer to the number of deaths due to injuries. Overall, road traffic causes more deaths than such traditional causes of concern as HIV, TB or malaria; road transport is in that sense a plague.

A third major concern is reduced physical activity and increased obesity. Physical inactivity is linked to our-car-dominated society and the urban sprawl that it encourages. Increased car use is associated with reduced physical activity and increased obesity, which results in more ill health and early deaths.

The mental and social health impacts arise in part from the sheer amount of time we spend in vehicles. In Canada, we spend about an hour a day in vehicles on average. A daily commute of one hour each way amounts to about 40 hours a month, or a full working week each month; this amounts to 40 hours a month that is not spent with family, friends and neighbours.

Morover, research has shown that stress levels – including salivary cortisol, a measurable marker of stress – increase as commuting time increases, but less so in those commuting by train rather than in cars. Importantly, one study showed that improved transit that led to reduced commute time also led to reduced stress.

Finally, all that gasoline used in driving is an important source of carbon dioxide, contributing to global warming and climate disruption, with all the negative health conequences that ensue.

So how can public transit improve this situation? First, it is a lot safer. The number of people killed per passenger mile is an order of magnitude (tenfold) smaller. Second, it’s a lot cleaner; less air pollution means fewer deaths and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Third, transit users walk and bike more, so are more physically active and fitter. Fourth, as noted above, transit use is less stressful, even if it does not necessarily reduce the length of time spent commuting.

Finally, transit plays an important social role we don’t often consider. It was former Toronto Mayor John Sewell who highlighted this for me in the 1980s, when he described Toronto’s public transit system as “the great democratizer”. By this he meant that everybody – young and old, rich and poor, black and white, male and female – literally rubbed shoulders with each other on a daily basis, and had to learn to get on with each other. It’s a very interesting way to think about public transit.

So if I were in Metro Vancouver, I would definitely be voting Yes in the transit referendum this month – it’s just good public health policy.

© Trevor Hancock, 2015

Originally posted on Times Colonist March 11, 2015

You don’t need to be an economist to understand how our current economic system is failing us.

Everyday we hear new stories locally and globally about rising unemployment rates, the widening gap between the rich and the poor, child poverty, terrorism and climate change.

In 2009, UK researchers Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett published what has been called a ‘sweeping theory of everything’ in their ground-breaking book The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone. Their work shows that levels of inequality significantly impact each of the following eleven different health and social problems: physical health, mental health, drug abuse, education, social mobility, trust and community life, violence, teenage pregnancies and children well-being. They argue that this inequality has eroded trust, increased anxiety and illness, and encouraged excessive consumption. Unfortunately, this is a global concern and outcomes are significantly worse in greater unequal societies.

Why do we live in world where 1 billion people wake up hungry? What have we proposed as solutions for this massive inequity? It seems to me that our well-intended solutions to date have allowed these levels of inequity to increase. But why?

Our society has grown to be very good at developing interventions, projects and programs to solve some of these pervasive social and health issues arising from our modern economical structures. In fact, the Honorable Monique Bégin, one of the champions of the Canada Health Act (known globally for the early foundations of a just and equitable health care system) has recognized that we live in a country of perpetual pilot projects that rarely move towards system change.

The current system has also isolated our advocacy efforts to address these social and health-related issues. For instance, recent activity in relation to violence prevention is a good example of how various efforts and resources are channelled to create awareness campaigns or community projects, without consideration of the collective impact of these often isolated initiatives. How can we eradicate violence if we are not addressing the complex, yet modifiable social, political, economic and environmental factors that are at its core?

We can’t rely on siloed approaches or interventions that target individual problems. How can we transform the way in which we view the root causes of these systemic issues?

If we look upstream for the ultimate cause of the economic crisis that is tearing so many lives apart, we find an illusion: the belief that money-a mere number created with a simple accounting entry that has no reality outside the human mind- is wealth. Because money represents a claim on so many things essential to our survival and well-being, we easily slip into evaluating economic performance in terms of the rate of financial return to money, essentially the rate at which money is growing, rather than by the economy’s contribution to the long-term well-being of people and nature (David C. Korten, 2009).

Fortunately, a global movement has emerged to change the measuring stick and the bar on how we measure progress that challenge the current economic system and GDP standards. New ways are emerging everyday. In essence, we are already creating a collective systemic shift towards wellbeing. In addition to the new measurement systems prioritizing quality of life, environmental sustainability, and corporate social responsibility, some governments are understanding that they need to invest in wellbeing. In fact, the British government recently announced a What Works Centre for Wellbeing, with initial funding of £3.5 million over three years to investigate the determinants of wellbeing and how to improve it. The business community is also very interested in how wellbeing of employees can improve the bottom line and there is a growing body of psychological and economic evidence around individual wellbeing.

However, in order for the shift towards wellbeing to reach the tipping point, we cannot continue to work in isolation from one another. We cannot address issues of inequity if we continue to work from old paradigms that reward competition and self –interests in pursuit of economic prosperity, as proposed by the 18th century priviledged western men who laid the foundations of the free market economic theory. Why not question these outdated theories that are not serving us today?

What if we shifted to a new paradigm that creates space for all of us to belong, and for sectors to come together? What if we prioritized caring, collaboration, empathy and compassion for one another, and importantly for ourselves.

Transformation starts with each and everyone of us, right now. However, a shift towards well-being and equity also means we need to create a space for women to lead us into the future before us. On this International Women’s day, I celebrate all women. I am grateful to those who came before us, who fearlessly fought for our right to vote and opened doors to higher education and the workforce, so that I can be writing these lines today. I am grateful for all those advocating for equal pay today and for the girls who are becoming the women of the future, with new ways of being, and new ways of creating wellbeing for all.

I can see a future where we all have opportunities to flourish, in a planet that is flourishing. Do you?

Paola Ardiles, Founder, Bridge for Health

Upcoming Events!

Thank you to those who participated in the discussion Paola Ardiles (Founder of Bridge for Health) led on how to Create Healthy and Happy Workplaces at Empower Health, Vancouver. This interactive discussion featured our brand new Healthy Business Action Framework that highlights various actions areas and examples of practices to promote wellbeing at work. This is a starting point for Bridge for Health and we look forward to your input. We are building on a model developed at Simon Fraser University. Below is a sneak preview:

Burnaby Monthly Community Talks

Join us for our next talk on Tuesday April 7th, 6:30-8pm for a discussion on How Intuition can Help you Reduce Stress, Worry and Anxiety with Joseph Eliezer, a Vancouver-based psychotherapist and registered counsellor, best selling author and public speaker. REGISTER TODAY!

Burnaby Public Library (easy access by skytrain and free parking) is supporting our community engagement strategy. If you would like to share your ideas/practice or research with the public, please get in touch with Charlene King our community engagement co-lead charlene@bridgeforhealth.org

Strategic Planning Update

Bridge for Health core team and global advisory group have been working on a strategic planning process for the last 6 months. We are excited to announce that Bridge for Health will operate as a social enterprise, with consulting and research services offered to support businesses committed to corporate social responsibility, to incorporate wellbeing into their business practices. The profits generated will be used to support the further development of our community engagement and advocacy work.

Over the next year there will all kinds of exciting opportunities for you to get involved.

We will be reaching out to industry partners and community members both in Canada and abroad, to ensure we continue to build the mission and vision of Bridge for Health. We would love to hear from you if you know others that share our passion for health and wellbeing for all.

If you are interested in any more information please contact us at:

info@bridgeforhealth.org

Volunteer Opportunities

In the meantime we find funding to set up our infrastructure, we will be recruiting volunteers to support our business planning, as well as the community/advocacy work. Please visit the website for updates on how to stay involved.

To stay tuned to immediate news and updates please LIKE us at facebook.com/Bridge4Health or follow us @Bridge4Health

We hope to connect with you soon!

Paola

Paola Ardiles, Founder Bridge for Health

on behalf of the core team and global advisory group.

It is a truism in population health work that the major determinants of our health lie beyond the health care system. Among the many professional groups whose work affects the health of people and communities, the design professions are among the most important.

By ‘design professions’ I mean architects, interior designers, engineers, landscape architects and urban planners. Their work has a significant impact on health, for better or for worse. In fact, I would argue that the most important evaluative measure of the outcome of their work is, or should be, whether it improves the health, wellbeing and quality of life of the people who live in the places they design.

One of our defining human characteristics is that we started to create shelters to protect us from the elements. Today, startlingly, we Canadians spend about 90% of our time indoors. Of the remaining 10%, half of it is spent in vehicles. This means we only spend on average an hour a day – about 5% of our time – outdoors.

When I present this information to my students and to audiences, it is usually met with expressions of surprise and disbelief. So if you find this surprising, I suggest you keep a time diary for a week and record where you spend your time; you will be surprised!

Not only do we live indoors, we now are urban dwellers. We began living in cities about 6,000 years ago and early in the 21st century, the world passed the point at which more than half of the population lives in urban areas. In Canada, we passed that point in the early 20th century, and now we are about 80% urbanized. Globally, we will be two-thirds urbanized by 2050.

Moreover, because we are 80% urbanized, we spend most of our one hour a day of outdoor time in an urban setting. So most of us spend very little time outdoors in non-urban natural areas – perhaps on average about 1% of our time. This is a problem because of the growing evidence that human wellbeing requires a connection with nature, and this is especially true for children.

Clearly the built environment is by far the most important physical environment for Canadians today, and indeed for the global population. Moreover, how we design and operate our built environment has important implications for the natural environment, affecting land use, air and water quality and natural ecosystems, which also affects our health. This makes the people who design our built environments very important shapers of our health and wellbeing. So here are some ways they can improve our health through improving our built environments.

First, we need to improve the quality of housing, especially for low-income populations, including many First Nations. The health costs of damp, unsafe and crowded housing are very high, both in human and in economic terms. In a country as wealthy as Canada, it is scandalous that in 2006, 45% of housing on First Nations’ reserves was in need of major repairs, compared to 7% for the non-Aboriginal population. The design professions need to work with social groups and governments to design simple, affordable, healthy and environmentally sustainable housing, especially for low-income and Aboriginal communities.

Second, we need to find ways to bring nature to people in the places where they lead their lives, especially in schools and neighbourhoods, but also in our workplaces. Street trees and green space help to reduce urban summer temperature, while neighbourhood parks, community gardens and school gardens can help create community connections as well.

Third, we need to stop creating urban sprawl. The health impacts of urban sprawl include decreased physical activity and increased obesity; more energy use, air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions; and more stress and loss of family time due to long commutes. More dense, mixed-use walkable communities can help offset many of these problems and lead to improved health, while being more environmentally sustainable.

The creation of more sustainable communities is itself good for health, because well-designed communities have a smaller ecological footprint. When we reduce harm to the environment, we reduce harm to ourselves.

If we truly care about the wellbeing of ourselves, our families and others, we need to design the buildings and neighbourhoods where we live, learn, work and play so that they maximize the health of the people in those places.

© Trevor Hancock, 2015

Published in the  Times Colonist Feb 19, 2015.

Times Colonist Feb 19, 2015.

By Dr. Trevor Hancock

How we measure progress hinges on what we mean by progress, and what business we think we are in, as a society and as governments. Too often, it seems the central purpose is to grow the economy, but I believe there is more to life than that.

How we measure progress hinges on what we mean by progress, and what business we think we are in, as a society and as governments. Too often, it seems the central purpose is to grow the economy, but I believe there is more to life than that.

We are – or should be – in the business of growing people, on maximising human rather than economic development. The economy, we need to understand, exists to serve human needs and human ends, not the other way around.

Last week I critiqued two of our main yardsticks for measuring progress. The GDP, which completely fails to distinguish between ‘good’ expenditures – things that add to human wellbeing, social development and ecological sustainability – and ‘bad’ expenditures that harm these outcomes; they are treated as the same. And life expectancy, which tells us a lot about those who die this year but nothing about the possible length of life of those born this year.

Consequently, we are navigating using the rearview mirror (because things improved in the past, they will in the future) and with misleading gauges. So what are the alternatives? Here I will focus on alternatives to GDP.

There are several leading contenders, with the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), the Happy Planet Index (HPI) and the Canadian Index of Wellbeing (CIW) as some of the better options.

The GPI starts with the same personal consumption data that the GDP is based on, but then makes some crucial distinctions. It adjusts for factors such as income distribution, adds factors such as the value of household and volunteer work, and subtracts factors such as the costs of crime and pollution.

A 2013 report by Redefining Progress (the Seattle-based NGO that created the GPI) compared the GDP and GPI for 17 countries (most of them high-income) for the period from 1955 to 2003. Troublingly, it found that while global GDP has increased more than three-fold since 1950, the GPI has actually decreased in those countries since 1978.

So while the GDP tells us we are doing better, the GPI tells us that is not so. What’s more, the study found that beyond about $7,000 GDP per person (Canada’s GDP per person was more than $50,000 in 2013), further increases in GDP per capita are negatively correlated with GPI. In other words, further growth in GDP does more harm than good.

The CIW tells a similar story. It tracks changes in eight quality of life categories. In the period from 1994 to 2010, while Canada’s GDP grew by 29%, our quality of life only improved by 5.7%. So increased GDP does not translate into a better quality of life.

Perhaps the most interesting of the alternatives is the HPI, developed by the New Economics Foundation in the UK. They describe it as “ the first index to combine environmental impact with well-being, ranking countries on how many long and happy lives they produce per unit of environmental input”. It measures the number of ‘happy’ life years, which is life expectancy adjusted for life satisfaction, and divides it by the ecological footprint.

The top three countries on the 2012 HPI are Costa Rica, Vietnam and Colombia. By comparison, Canada places 65th, with a life expectancy and level of experienced wellbeing not much higher than that of Costa Rica but an ecological footprint more than 2.5 times as large.

But while provincial and federal governments and international organisations still largely use GDP as their main way of measuring progress, municipal governments do not. In all my Healthy Cities work over almost 30 years with municipal governments in Canada and around the world, I have never seen one that measured GDP or used it as a marker of progress.

Municipal governments seem to understand that measuring progress is about much more than the economy, that it’s about the lived experience of people in their communities. So they almost always use some version of a measurement of quality of life. In fact the Federation of Canadian Municipalities has had a Quality of Life measuring system for 20 years or more.

Here in Victoria, the Vital Signs report from the Victoria Foundation is an example of this approach, and is based on the CIW.

It is time the higher levels of governments took a lesson from municipal governments, and from the knowledge we now have, and started measuring progress in more all-encompassing and realistic ways.

© Trevor Hancock, 2015

Originally published in Times Colonist Feb 4, 2015

In the world of population and public health in which I work, we have paid great attention in recent years to what are termed the ‘social determinants of health’. Poverty and all its attendant ills – food insecurity, poor and insecure housing, low levels of education, marginal, tenuous and unhealthy jobs and others – have been our focus.

But in focusing on these issues, we have neglected the most important determinants of our health. Because like all other animal species we need air, water and food to survive, as well as other vital ecosystem ‘services’. In addition, we depend on nature for fuel and materials and a relatively stable climate system. Functioning ecosystems are the most fundamental determinants of health, without which human societies and perhaps even humanity itself will fail.

In which case, we are in trouble, as several recent reports have reminded us.

The World Wide Fund for Nature released its bi-annual Living Planet Report in the fall of 2014. They found that the Living Planet Index, “which measures more than 10,000 representative populations of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish, has declined by 52 per cent since 1970”.

The same publication, using the Ecological Footprint, reported that the global Footprint has more than doubled in the past 50 years and that “We would need the regenerative capacity of 1.5 Earths to provide the ecological services we currently use.” If the whole world lived at the same level of consumption as we do in rich countries, we would need several more planets to meet our needs!

In November 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported that “Human influence on the climate system is clear, and recent [human-created] emissions of greenhouse gases are the highest in history. Recent climate changes have had widespread impacts on human and natural systems.”

Just this past week, a group of ocean scientists published a report in Science in which they examined the extent of damage to marine species globally. A combination of overfishing, destruction of habitat, global warming, ocean acidification and pollution has already had a dramatic impact on sea life. They caution that if we continue as we are, we risk “a major extinction pulse, similar to that observed on land during the industrial revolution, as the footprint of human ocean use widens”.

Also this past week, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported that 2014 was the hottest year in the 135 years of recording; December was the hottest on record, and that was the case for 5 other months in 2014.

In short, four great human-created driving forces are converging, threatening the stability of our ecosystems: Climate and atmospheric change, pollution and ecotoxicity, depletion of renewable and non-renewable resources, and the loss of habitat, species and biodiversity. The ecological changes that we are creating are undermining and threatening our health and the stability and continuity of societies around the world.

For example, we can expect to see health impacts due to climate change. These will result from rising sea-levels flooding low-lying land; changes in the distribution of insects that transmit diseases such as malaria; changes in water supply and agricultural ecosystems, and also in oceans, affecting food supply; and more extreme weather events. All this will also result in large-scale migration of eco-refugees, with all the associated health concerns that raises.

That is why there has been growing attention to the ecological determinants of health in recent years. In fact, I am leading a two and a half year project for the Canadian Public Health Association to document the threats to health posed by these human-induced ecological changes, and to suggest the actions we need to take to address them. Our report will be out this spring.

More recently, at a global level, The Lancet – one of the world’s leading medical journals – published a manifesto for planetary health in March 2014, noting our responsibility as health professionals to “respond to the fragility of our planet and our obligation to safeguard the physical and human environments within which we exist.” Now an international Commission, supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, is developing a report on Planetary Health that will be released this summer.

Because when you come right down to it, we can’t have healthy people on an unhealthy planet. But we are making our planet sick, and it can’t go on.

© Trevor Hancock, 2015

Originally Published in the Times Colonist 22 Jan, 2015